Guest Reviewer – Charlie Moores

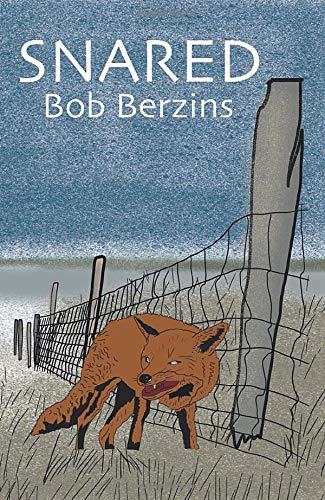

| Snared | By Bob Berzin | Independently published | 2020 | Paperback | 345 Pages | ISBN 9798643295204 |

If you’ve ever read Mark Avery’s influential (and hugely popular) blog, (and if not, why not?) you may recognise Bob Berzins’ name. He has made several contributions in the form of guest posts over the last few years, commenting in depth on environmental damage caused by the grouse shooting industry to his beloved uplands (see for example ‘Blanket bog burning: what’s planned?’ or ‘Grouse Shooting, a Track and the Law‘). Readers’ comments below the posts commend Bob on his research, his knowledge of the moorlands, and his insight and persistence.

Bob Berzin

That knowledge and insight have come from many years exploring the area’s grouse moors. Born near Leeds, trained and working in counselling and psychotherapy, Bob has spent much of his life first climbing in the Peak District before then taking up fell running. Covering huge areas of moorland, he became increasingly aware in his forties how the uplands were changing as grouse shooting intensified. He remembers his first encounter with ‘illegal’ activity was of finding two gamekeepers on top of the stunning Alport Castles (a well known Peregrine nest site on National Trust land), one of whom was lying in the grass with a rifle. Bob reported the incident to the RSPB and the Police. He also began to see more burning and predator control, the laying out of medicated grit, and an alarming growth in the number of snares left lying in wait for foxes.

Ah, snares. Many of us had (naively) assumed that by the turn of the century snares were illegal or still used only by a few old-school poachers trapping rabbits, but it turned out that once we started looking for them they were in fact everywhere. Or at least everywhere that intensive shooting had set out its stall. How widespread became apparent when reports began to appear of pets being caught in snares. Of ‘non-target animals’ like badgers, which have the highest level of protection in law, being caught (the header image used here is taken from footage Bob himself filmed on a moor). It perhaps took mainstream media reports of fell runners in the Peak District being snagged in snares set close to footpaths to really focus attention on this indiscriminate and cruel form of ‘control’: Bob himself was quoted in a 2015 BBC News article saying, “This was open-access land and in my opinion the snares weren’t properly marked and there were no notices. They should be banned.” Far from being banned, of course, a self-styled (and self-serving) Code of Practice on snaring was handed to the shooting industry instead. As you read this uncountable numbers of snares are still being ‘legally’ operated the length and breadth of Britain…

Meanwhile Bob was still out on the Peaks. By now he had become active in a grassroots monitoring network, created, he says, “out of demand from local people in rural areas who were fed up with sterile burnt grouse moors devoid of wildlife, but were too afraid of intimidation if they speak out in their community“. He felt though he needed to do more, deciding to take all his experience, his intimate knowledge of the uplands, his deep dislike of snares and other animal traps, add them to the burgeoning writing skills evident in those previous guest posts, and turn them into a hard-hitting novel, ‘Snared’, a book which he says “exposes the pressures of rural life and tackles the brutal reality of countryside crime“.

Does ‘Snared’ do that? Unequivocally, yes. In fact I think that ‘Snared’ absolutely nails the unsavoury workings of the intensive grouse shooting industry to the wall. While carrying the usual legal disclaimer that ‘any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental’, the book is packed with evocative descriptions of the uplands and the people that live there – from venal estate owners to lawless badger baiters and angry, violent gamekeepers locked in battles with their families and the local wildlife. It feels authentic from the first line to the last.

That last paragraph may perhaps make ‘Snared’ sound as if it could be written off as two-dimensional. Far from being an exaggerated and romanticised ‘townie’ view of the moors and the people who live there, though, ‘Snared’ is fully-rounded and feels absolutely real. If you’ve been to the uplands you will recognise every description. If you haven’t ‘Snared’ will take you there – and make you weep in frustration about how a minority interest has defiled such an extraordinarily beautiful area. It details (in occasionally adult language) the planned destruction of nationally-important habitats, the routine killing of wildlife in the name of ‘protecting’ so-called ‘gamebirds’, the demand for profit above all else – including above adherence to the law. And, boy, how the law is ignored, sidestepped, or dismissed in ‘Snared’. The industry will no doubt step in at this point and say that ‘Snared’ is nothing more than an attack by a member of the ‘anti-shooting brigade’ (or what they habitually label ‘an animal rights extremist’), but the drive to deliver raptor-free shooting is borne out by the extensive illegal persecution of birds of prey that has – with perfect timing – been highlighted by the RSPB Investigations Unit and a Channel 4 documentary which both point to an explosion in wildlife crime during Covid-19 lockdown (when the absence of ‘prying eyes’ has apparently allowed gamekeepers free rein).

While the landscapes and wildlife issues are treated expertly (which perhaps should be a given as he has been steeped in them for most of his life), Bob also handles his human characters far better than you might expect from a first-timer who (as he tells us in a guest blog tomorrow) has “had to learn how to be a writer“. From the boorish estate owner to the activist and his partner who monitors the local uplands and who uncovers the truth about persecution and the huge number of snares being used, from Cathy, the anxious and abused (but ultimately determined and strong) gamekeeper’s wife, to the gamekeeper himself, the people that populate ‘Snared’ are drawn from experience. Bob, over the years, has clearly met versions of all them and created amalgams that feel undeniably truthful.

That’s particularly true, in my opinion anyway, for the character of the head gamekeeper John. When Bob first sent me a pre-publication edit of ‘Snared’ I mailed back saying that no ‘ifs’ or ‘buts’ I really enjoyed the book (I read it one session which means I was still engaged long after the working day was over!), and that I especially appreciated that he hadn’t watered down John’s volatile, tense, and generally unpleasant characterisation by making some inauthentic attempt to excuse his aggression through his upbringing or some vague suggestion that he is somehow a ‘victim’ himself. John is indeed ‘made’ by his surroundings, and feels he has little choice to break the law for his employer, but social media is full of real-life ‘Johns’, shooting their mouths off, glorying in their role of slaughtering wildlife, telling the rest of us to ‘man up’ or ‘get a grip’, and proud of the heritage of raptor persecution they sneeringly hint at continuing. As Bob writes of John, “He thought of himself as a man of nature“, but John and his ilk are nothing of the sort: they are destroyers of nature, unaware of just how little they know, stunted by an icy hatred of anyone who disagrees with them. ‘John’ is, of course, a fiction, a product of Bob’s imagination, but ‘Snared’ is all the better for his resolutely unsympathetic portrayal.

It’s likely that the driven grouse industry will hate every line of ‘Snared’, but Bob Berzins knows what he is talking about, and his experiences on the ground have been condensed into this powerful story. Every paragraph, every wildlife crime, every environmental sacrilege, and every abuse of privilege and power rings true. Before reading ‘Snared’ I was a little concerned that I might have had to fall back on the ‘For a first-time effort this shows promise‘ backhanded compliment that we all know means ‘avoid‘ – especially given how important the subject was to me personally – but this is an extremely well-written book, with a pacy, multi-threaded plot at its core. It will hold your attention from start to finish, and with very well-written passages focussing on the acidic drip of mental and physical abuse will (especially as the tension builds in the final third of the book) keep you on the edge of your seat.

Will ‘Snared’ bring an end to the driven grouse shooting industry or even to the use of metal nooses as the public demands? Perhaps not on its own, no, but it will substantially add to the pressure that is being heaped on grouse shooting and ‘Snared’ deserves to stand alongside such renowned but different dissections of this hideous blood-fest as Mark Avery’s analytical Inglorious and Gill Lewis’s Eagle Warrior, a novel aimed at young adults.

On top of which, all profits from ‘Snared’ will be going to a domestic abuse charity: a decision that was made in recognition of the suffering that is hidden away in some rural communities, and which is both skillfully depicted through the tension between John and his family that builds throughout ‘Snared’ and (in case the lobbyists want to cry foul) revealed in a report, Captive and Controlled, published by the National Rural Crime Network.

Not donating to a conservation charity is perhaps a surprising move, but then as I’ve discovered over the last few weeks of talking with Bob and working out how The War on Wildlife Project can help promote his work, Bob doesn’t conform to the norm – and all of us who love wildlife and who want to see an end to the massacre on the moorlands should be very grateful for that indeed.