Ian Sinclair – The pioneer of African birding

By Chris Lotz – Birding Ecotours

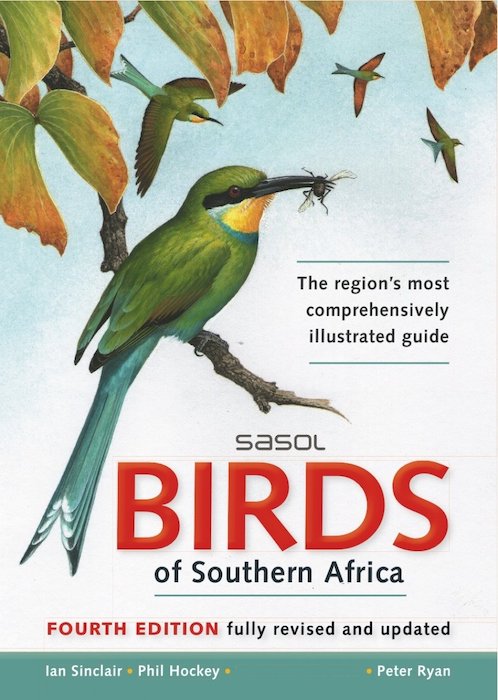

Born in Northern Ireland but spending a large part of his life in South Africa, Ian Sinclair pioneered the early birding landscape of South Africa. And, indeed, of the rest of the vast African continent. Long before birding became a popular pastime in South Africa, Ian was already out there getting people excited about it. He’s always been a prolific bird book author. He was originally the lead author of the best-selling field guide, Sasol birds of southern Africa, which covers 6.5 countries south of the Kunene and Zambezi Rivers (only the southern half of Mozambique is covered, hence the inclusion of a half country here). This, southern Africa (rather than South Africa, more on that later in this article), became the main listing region for South African birders, partly because of Ian’s constant encouragement (although started by Austin Roberts’ original field guide). Until recently, the only easily available field guide for Madagascar was also by Ian Sinclair (as first author).

More influential (to me anyway) than Ian’s field guides, was his classic bird-finding guide Where to watch birds in southern Africa, though. The writings within this book made exploring the far corners of the region almost impossible to resist. When I was a child, many statements from this book were just so tantalizing. Luckily, my parents liked to travel, so I was actually able to use this book to suggest and then plan many of our family holidays to places like Namibia and Zimbabwe. My parents would enjoy the landscapes and African megafauna, and I’d find life-birds, thanks to the bird-finding information contained in this book (I’m not so sure my siblings enjoyed all the travel to these remote areas though!). I loved statements from this book such as “An area enticingly but frustratingly stocked with specials beyond the grasp of the southern African birder” (describing a part of central Mozambique). And, “This is the only place where Woodward’s Barbet is know to occur. A loud ‘chop’ overhead heralds the presence of this chunky green bird which stays high up in the trees”. (describing Ongoye Forest in Kwazulu/Natal).

My top favourite statement from this book, however, was, “The Spitzkop is one place where the rare endemic Herero Chat can be ticked with certainty around the bases of the granite hills” (describing a huge batholith that rises straight out of the desert plain in the middle of the Namib desert). Unfortunately, I soon learned that the statement wasn’t as simple as it seemed. We pitched up there, thinking Herero Chats would be everywhere. But we dipped it completely! And, so many birders miss the species, as there’s actually nowhere its predictable enough to near-guarantee. It’s a tough bird, even though, granted, this is one of the best places on earth for it. I now interpret the statement by Ian Sinclair that “if you’re Ian Sinclair or another very experienced birding guide who has learned exactly where to look for Herero Chats within the rather large Spitzkop area, you’ll probably manage to find it if you have at least four hours available in the area”. I’ve subsequently learned a few stakeouts for this species around there. And I usually find it with quite some effort, but I also have backup sites away from the Spitzkop, in case we miss it there on any particular trip. I did just want to mention that sometimes this is a ‘drive-up bird’ which is at the first stakeout one arrives at – so for those who found it easy when they went there, “…you were just lucky, OK?”

In my humble opinion, Ian’s biggest contribution to African birding came quite late, after he’d written a plethora of other books and stirred up the twitching scene in southern Africa (more about that later). Ian decided to write a continent-wide book (along with co-author Peter Ryan), Birds of Africa south of the Sahara: a comprehensive illustrated field guide. Well, not quite continent-wide, but the ‘real’ Africa does lie south of the Sahara, doesn’t it? This incredible (and rather large) field guide covers the world’s second biggest continent, and was perhaps a whole order of magnitude more ambitious than any field guide for any smaller part of Africa that had previously been published (including such classics as The birds of the Horn of Africa. The amazing thing about this book is that it tantalizes and encourages a birder to get out there into Africa and see its dazzling birds.

Quite a number of birders I know suddenly got a new favourite bird, Yellow-crested Helmet-shrike, which they didn’t even know existed prior to the publication of this Africa-wide field guide. What an unbelievably beautiful bird – described by the authors as follows: “…the slightly glossy-black plumage relieved only by a brilliant golden crest makes this species unmistakable”. But this is a near-mythical bird. What are the chances of any of us ever actually seeing a bird that only occurs in a part of the Albertine (Western) Rift Valley that’s within the war-torn Congo? (and being destroyed very fast).

The book, also illustrates so many turacos, mousebirds, bush-shrikes, sunbirds, etc., and so showcases what the African continent has to offer, often off the beaten track and away from the relatively well-birded eastern and southern African regions. Any serious birder will want to travel the continent, after paging through this remarkable field guide, which now covers humungous swathes of land few birders ever knew about – e.g. south-central Africa – see a detailed article about this area here, and even more so, central Africa proper – the vast region west of Uganda. This birding guide to all sub-Saharan African birds, is one in which the authors follow their own taxonomy – splitting like crazy, but that again only showcases what might be possible, as indeed the birding world is tending towards splitting more and more these days.

Starting my birding career pre-internet, and long before any social media, Ian Sinclair influenced me massively with classic old books (or what I now call old, now that I’m 46 years old – not so when I was a child). Another book was Ian’s photographic guide to birds of southern Africa. This was in the days before digital photography, yet Ian managed to generate a book with a photo of almost every southern African species. The few species where he had to substitute a painting, only highlighted the rarity and mystery factor. But basically, this book allowed me to see what many of the birds I still ‘needed’ actually looked like (rather than relying on paintings, which naturally are not as accurate as photos).

It wasn’t only this books that influenced me. As a child, I attended a weekend birding course run by Ian, which that managed to get me even more excited about birding than I already was. In typical Ian Sinclair fashion, he described Red-chested Flufftail as “a very common bird, abundant actually”. Who had ever seen a flufftail? Basically no-one, because they must be the world’s most elusive birds, virtually never allowing visuals. Of course, Ian was correct in that statement, as Red-chested Flufftails do abound, even in tiny small-farm dams, not to mention all the extensive marshes around Cape Town, Johannesburg, Durban and all over southern Africa. But statements like that made us think; none of us had seen a flufftail, yet they’re actually very common?

Ian also largely pioneered the twitching scene in southern Africa. He focused on the whole region south of the Zambezi and Kunene Rivers, rather than just on southern Africa. He showed us that it was possible to see 800 species within this region. Then he actually proved to us that seeing 800 species in a single year was also possible! He was the first (that I am aware of) to attempt a Big Year in this region. And later, he showed us that 900 life-birds was possible within southern Africa, as he was the first to reach this previously unheard-of number! There are now an amazing ten people shown as having seen over 900 species in southern Africa, see the classic website Zest For Birds Take a look at the top of the ‘700 club’. And you’ll note the statement with Ian’s name that he’s “retired from southern African birding”. That’s true, but what a legend he was, in his time!

Ian now keeps quite a low profile. You’ll rarely see him on social media, unlike all the young birders who were born after Ian had already pioneered the early birding scene in southern Africa.

The great thing is that birding has become immensely popular among young birders, including kids. That was not the case in Ian’s day (or in my day when I was a child). Social media probably plays a big role in this. It’s now so easy to get digital photos and post them on Instagram or Facebook. But Ian was born in a different era, when bird photography was difficult, and when the closest thing to social media was rare bird land line numbers one could call.